Penicillin is considered one of the greatest achievements in medicine. This antibiotic allowed doctors to successfully treat and cure patients with deadly infectious diseases. Its discovery came by accident, its development involved many people, and its ability to be widely used for treating patients can be traced back to one moldy cantaloupe.

The First Discovery

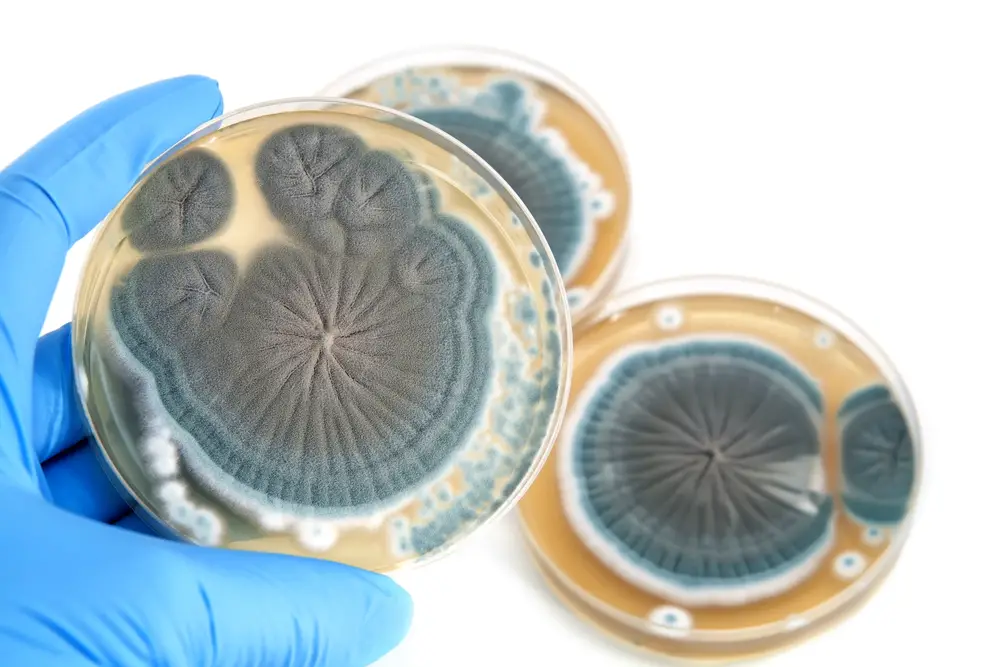

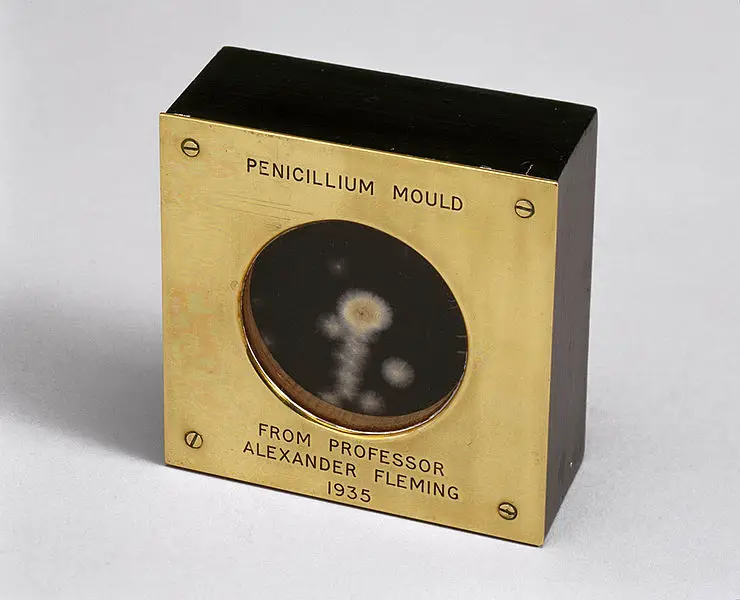

Dr. Alexander Fleming, a professor of bacteriology at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, returned from a vacation in September of 1928 to find that Petri dishes containing colonies of Staphylococcus aureus had areas clear of bacteria where a mold was growing. He looked at the dishes under a microscope and discovered that the mold prevented the Staphylococcus from growing further.

He identified the mold as Penicillium notatum and named the active component “penicillin.” He tried growing other molds but found that only the Penicillium notatum stopped the growth of this bacteria, as well as others. Fleming concluded that there was something particular in that mold that was able to kill the bacteria, and the world’s first antibiotic was born. But he was unable to purify and find the exact essential killer component, and after ending his studies on it in 1931, he agreed to send it to anyone who could take on the problem.

Researchers at Oxford University Isolate Penicillin

Dr. Ernst Chain, and his supervisor, Dr. Howard Florey, found Fleming’s 1929 journal article about his findings and decided to try to isolate the active compound in penicillin. In 1939, they brought on Dr. Norman Heatley, a fungal expert. Heatley began growing Penicillium in large amounts, and Chain successfully purified penicillin from the mold. They then tested the penicillin in mice to see its effects.

On May 25, 1939, they injected mice with the bacteria Streptococcus and others with penicillin. The next morning, the mice that had been injected with Streptococcus were dead, and the mice given penicillin were still alive. Chain said the results were “a miracle.” They published their findings in The Lancet in August 1940.

The team next moved on to test the clinical effectiveness of penicillin in humans after they had enough of it purified. The first person to receive penicillin was a 43-year-old Oxford policeman named Albert Alexander in February 1941. He had been injured in a bombing raid and had infected wounds. After only 24 hours, his condition began to improve, but because the supply of the purified penicillin was so low (Penicillium notatum yielded very little of its active component), Alexander was unable to be treated thoroughly and died a few weeks later.

The researchers published their findings, but because of World War II, Great Britain was unable to produce penicillin in the vast quantities that would be needed to treat patients successfully. This led to the United States’s involvement in the mass production of penicillin and another chance discovery.

The United States Gets Involved, As Well As a Cantaloupe

Florey and Heatly flew to the United States in June 1941 to secure a way to produce penicillin on a large scale. They were first referred to Robert Thom of the Department of Agriculture, an expert on the Penicillium mold, and then to the department’s Northern Regional Research Laboratory in Peoria, Illinois. Thom had in his collection of 1,000 Penicillium strains only two that produced penicillin, one of those being Penicillium notatum.

Two thousand liters of fluid from the Penicillium notatum mold cultures were needed to produce enough pure penicillin to treat a single person. A better, more productive mold was needed, and soil samples were sent to the laboratory from around the world. It just so happened that the mold that was needed was in the same city as the lab.

One day, a laboratory assistant named Betty Hunt brought in a cantaloupe she had picked up at the market, and it was covered in a “golden mold.” When the mold was tested, it was discovered to be a different strain called Penicillium chrysogenum and yielded six times more penicillin than the originally discovered mold, Penicillium notatum. The yield of this cantaloupe strain of mold was further increased when a mutant strain was produced with the use of x-rays and even more later when it was exposed to ultraviolet radiation.

The pharmaceutical companies in the United States were initially hesitant to take on the large-scale production of penicillin, but that changed when the U.S. was plunged into World War II after the Pearl Harbor attack later that year. At a meeting of the major pharmaceutical companies, which included Merck, Squibb, Pfizer, and Lederle, only ten days after Pearl Harbor, they were in agreement that they would research it independently but would give developments to the Committee on Medical Research, who would make the information more widely available.

Ramping up Production

By March 1942, the collaborative efforts of the companies had produced enough penicillin to use on the first patient, an American named Ann Miller in Connecticut. She was treated with penicillin due to blood poisoning from an infection and survived. Another ten cases were treated by June 1942.

By the end of 1942, there still was only enough penicillin to treat less than 100 patients, but in less than a year, because of continued research, development, and sharing of information and techniques by the pharmaceuticals, there was enough penicillin in stock to satisfy the demands of the Allied Armed Forces fighting in World War II. On March 1, 1944, Pfizer opened the first commercial plant in Brooklyn, New York, for the large-scale production of penicillin. By the end of the war, 650 billion units a month were being produced by pharmaceutical companies in the United States.

The Awards

Fleming, Florey, and Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945. In Fleming’s acceptance speech, he warned how the overuse of penicillin might lead to bacterial resistance, a problem that occurs today. Heatley was absent from that award, but in 1990, Oxford University awarded him an honorary doctorate of medicine, the first in its 800-year history.

The discovery of penicillin can’t really be traced to one discovery but a series of events that took place to get it to where it is today. Fleming discovered the accidental contamination of his culture in his lab, the Oxford researchers discovered how to process penicillin mold that could be used on people, and World War II spurred the large-scale production of penicillin that came from the chance a lab assistant brought in a cantaloupe with just the right strain of mold to make that happen.

Sources: ACS, Sanger Institute, New Scientist, PBS, Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal, University of Oxford, Science Museum UK, The Conversation