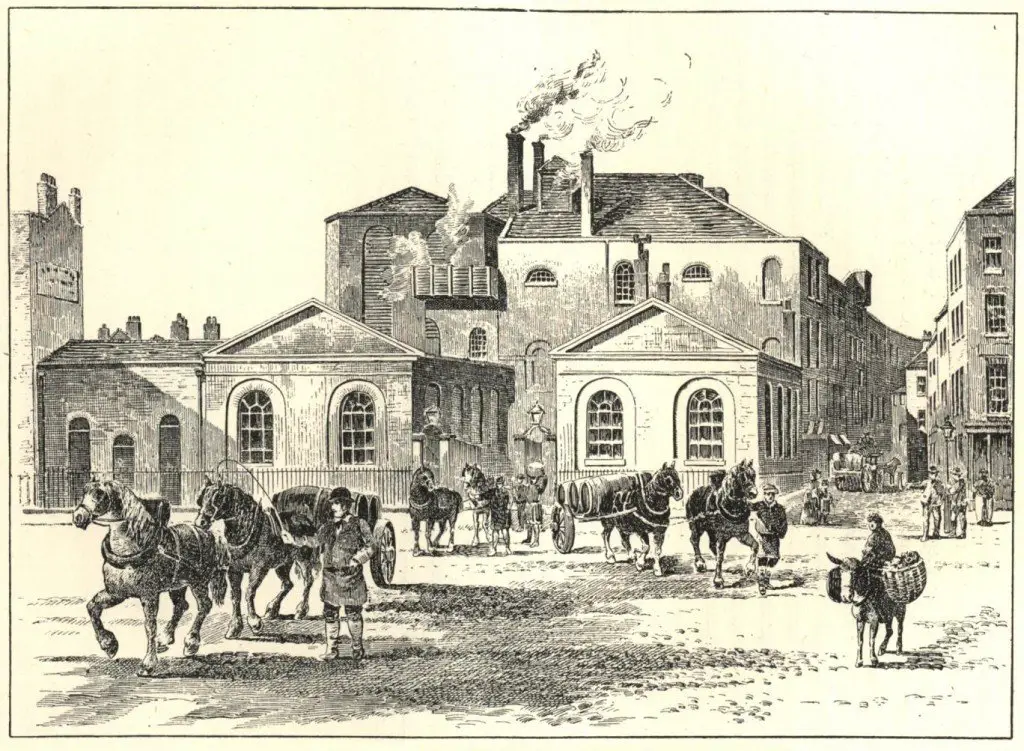

On October 17, 1814, in London, England, a strange disaster occurred that took the lives of eight people. A huge vat of beer burst in the Horse Shoe Brewery and sent a flood into the streets and the nearby dwellings of St. Giles Rookery, a poor area of the city.

Meux and Company, which owned the Horse Shoe Brewery, had installed a 22-foot high wooden fermentation tank in 1810. The vat was held together by giant iron rings. This vat was believed to hold about 3,500 barrels of brown porter ale in it, though some estimates have said the amount of beer could have been even higher.

On the afternoon of October 7, 1814, a storehouse clerk named George Crick inspected the tank and found that one of the iron rings (that weighed about 700 pounds each) had slipped and was off the side of the cask. This was not an unusual occurrence to Crick as the same thing had happened two or three times a year. Crick informed his superior, who didn’t think it was of concern, and told Crick to write a letter that a ring had slipped so an employee of the brewery could fix it at some later time.

About an hour after the inspection, however, there was a loud explosion inside the brewery. The tank had ruptured and shot the hot beer from the rear of the vat. The force of the liquid was so much that it shattered the tank in pieces and blew a hole in the back wall of the brewery that was made of a thick layer of brick. The force from the beer explosion also caused other vats nearby to break open, sending even more beer into the brewery and out in the street.

There was now a tsunami of beer cascading in the tight streets and densely populated area of St. Giles Rookery. The amount of beer that flowed from the brewery was estimated at 320,000 gallons, making a 15-foot high wave, and it started crashing into the underground cellars of buildings where many people lived.

A mother and her daughter were killed in one basement while four mourners attending a wake in another basement were also killed. Two others lost their lives in the subsequent flood. Four workers of the brewery were rescued.

In the aftermath, people began searching through the wreckage for survivors, trying to listen to anyone they could hear that needed help. The stench of beer reportedly lasted for months. Some rumors started to surface that as the beer flooded the street, many people began scooping it up in whatever they could find to hold it or just began drinking it while it was still in the streets. Based on newspaper reports from that time, those events likely never happened.

After the beer was cleaned up from the streets, it was reported that the brewery received a waiver from the British Parliament on taxes it had paid on the beer that had burst from the vat. This meant that any new beer it brewed in the amount that had been lost wouldn’t be taxed.

Meux and Company were taken to court for the accident, but jurors ruled it “an Act of God,” and the families of those that died received no compensation. The accident cost the brewery £23,000 (approx. £1.25 million today) but was saved from bankruptcy due to the decision to waive the excise tax on the beer that was lost.

The Horseshoe Brewery returned to business soon after and stayed at the site until 1921 before moving to a new location in Wandsworth, a district in south London.

Sources: Historic UK, Smithsonian Magazine, The History Press UK