The women involved in the American Revolutionary War didn’t just stand on the sidelines when the men went to battle. They were firmly entrenched in the fight for independence and participated in a number of different ways.

Some women took care of sick and injured soldiers, managed the households or ran the farms, or contributed to supplying the war effort. Others acted as spies, information gathers, messengers, and even fought in the battles of the war.

All the contributions by women in the war are too numerous to mention, but it is clear that without the colonial women’s engagement in the war, America would have never won its war for independence. Here are a few of those women’s stories.

The Mother of the Boston Tea Party

Sarah Fulton is known as the “Mother of the Boston Tea Party.” She came up with the idea for the men of the Boston Tea Party to disguise themselves as Mohawk Indians in 1773 and disposed of their disguises after the Tea Party was over. She also removed the red paint from the faces of the men so they wouldn’t be identified. Two years later, Fulton set up a field hospital after the battle at Bunker Hill and tended to wounded soldiers. But she wasn’t done there. In March 1776, Fulton traveled through enemy lines alone to deliver a message to General Washington.

The Female Paul Revere

Sybil Ludington has come to be known as the female Paul Revere. Ludington was only 16-years-old when she rode 40 miles to warn the New York militia that the British were moving and had burned Danbury, Connecticut. Her ride was two years after Revere’s famous ride in 1777, but she covered twice the distance, went through hostile territory, and did it all while it was raining.

The Woman Soldier

Deborah Sampson had been forced into life as an indentured servant from the age of 10 to the age of 18 when her father hadn’t returned from a sea voyage, which thrust the family into poverty. After her indentured servitude was complete, Sampson worked as a teacher. It was an amazing feat since Sampson had educated herself.

In 1782, Sampson joined in the fight for independence, but she did it in an unusual way. She disguised herself as a man and joined the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. Stafford was now Robert Shurtleff and part of an infantry company. She fought in New York and was wounded in battle there when she received a gash across the face from a sword. A few weeks later, Sampson was wounded by the shot of a musket ball and even tried to remove it herself so as not to be discovered.

After she was transferred to Philadelphia, Sampson became ill with a high fever and became unconscious. When she was taken to the hospital, Dr. Barnabas Binney tended to her and discovered her true identity, though he didn’t report her. He instead helped her continue to conceal her identity as she healed, but the continued ruse didn’t last long.

Sampson’s commanding officer, General John Patterson, was notified, and he sent the news to General Henry Knox, who sent it to General George Washington. Washington ordered that Sampson be honorably discharged, and this was completed on October 25, 1783. Sampson continued to fight for a military pension but was unsuccessful. She next went on a lecture tour starting in 1802 and finally received a military pension in 1805. Paul Revere had been one of her supporters that she should be secured with a pension.

The Guardian of the Bridge

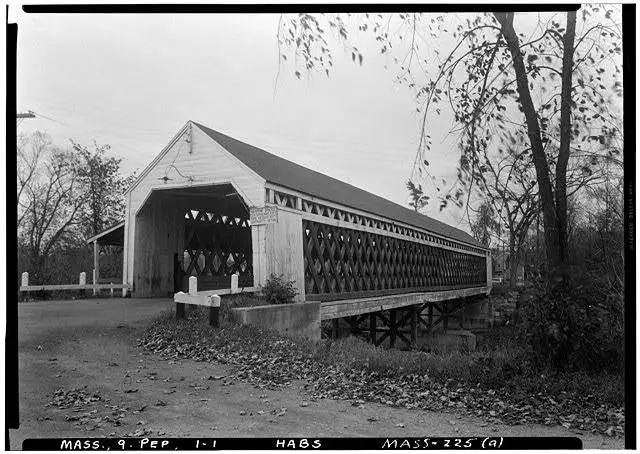

Prudence Cummings Wright formed a local militia in Pepperell, Massachusetts, in 1775 after the men had left for war. She became known as the “Guardian of the Bridge” when she and around 30 to 40 other women decided to stand guard at Jewett’s bridge, a bridge that led into their area.

Wright and her group were credited with capturing two Tory spies at the bridge one night. After they searched the men, the women found information going to the British General in Boston. The details of the story vary, but one of the spies was believed to be her brother, according to some accounts. The women of the militia, led by Wright, marched the men back to the town where they were held.

A Patriot Spy

Lydia Darragh was a Patriot spy during the Revolutionary War. After the British marched into Philadelphia in 1777, British General Sir William Howe made his camp across from the home of Darragh. She began to spy on General Howe and used her fourteen-year-old son to pass notes to her oldest son Charles, a Revolutionary soldier.

Near the end of 1777, the British began using Darragh’s home for meetings. Darragh was allowed to stay in her home while her young children were sent to live with relatives. In early December 1777, British officers held a secret meeting. Darragh was told to stay in her room, but she hid in a closet adjacent to the room where the meeting was being held. She overheard the British planning to make a surprise attack on Whitemarsh and Washington’s army.

Darragh received a pass under the guise that she would get flour from the mill and visit her children. She instead went to the Rising Sun Tavern, where she was able to pass her account of the meeting on to a Patriot officer. The message allowed Washington to prepare his troops for the attack, which resulted in a stalemate.

The British, believing their plans had been leaked, began to question people, including Darragh, who told them that she and her family had been asleep during the meeting. The British left Philadelphia in June 1778, and Darragh’s children returned to her home. Her message had likely fended off a victory by the British army and allowed the revolutionary troops to reach Valley Forge.

The Artist Spy

When Patience Wright’s husband died in 1769, she found herself without an income and a family to support. Needing a new source of income, Wright returned to something she did as a child — sculpting. She began to work with her sister Rachel Wells making life-like wax figures. The pair opened a waxworks in Philadelphia in 1770 and one in New York City, but a fire destroyed the New York waxwork in 1771 and all of Wright’s sculptures.

Wright decided to relocate to London for a new start and soon met Jane Mecom, Benjamin Franklin’s sister. Mecom introduced Wright to those in the high society of London, and the artist soon became popular. She began to sculpt many of London’s elite in wax, which included King George of England. She felt so comfortable with the English royals that she even discussed her support of independence for the colonies.

She first began to write to Benjamin Franklin about what she was hearing during sculpting sessions. She began to hide letters in her wax sculptures that were being shipped to America and the leaders of the revolution. Her popularity soon waned after the war began, however, since she didn’t hide her political views. She moved to Paris in 1780 and returned to London in 1782. She later asked to make a sculpture of George Washington in 1783, and he agreed, but it took a year for the letter to get into Washington’s hands. She died in 1786 before she got to sculpt the future president of the United States.

The Beloved Woman

Nanyehi, who was later known as Nancy Ward, was a Cherokee leader who supported the colonists during the Revolutionary War. Nanyehi’s story started in 1755 when she fought with her husband Kingfisher against the Creeks in the Battle of Taliwa in Georgia. After her husband was killed during the fight, she rallied her fellow Cherokees, charged the enemy, and was victorious in the battle. Because of her bravery, she was given the name Ghighau, or “Beloved Woman.”

This position was powerful because the Cherokee believed the Great Spirit could speak through the Beloved Woman. She was the head of the Women’s Council and sat on the Council of Chiefs, two very important positions in tribal affairs.

Nanyehi later married a British man named Bryant Ward and changed her name to Nancy Ward. She believed that violence wasn’t the answer to the encroachment on Cherokee lands by white settlers and instead advocated coexistence and compromise. She even warned white settlers about possible attacks from her fellow Cherokee in order to keep the peace.

When the Revolutionary War began, many Cherokee were on the side of the British and attacked the colonists, but Ward remained on the side of the colonists and advocated peace. She once again warned the colonists against an impending attack. Ward later helped to negotiate a peace treaty between the new United States and the Cherokee nation in 1785. Ultimately, the treaty never held, and by 1819, the lands she and her people were on were sold, and she was forced to move. She died in 1822 in Tennessee.

Look for Part Two of The Women of the Revolutionary War coming soon.

Sources: Boston Tea Party Ship (1), History.org, Womens’ History (1), Womens’ History (2), Women History Blog (1), Womens’ History (4), PSU.org, History of Massachusetts, Shop Pepperell, Boston Tea Party Ship (2), NWHM.org, National Archives (2)