Breaches of the high-security area surrounding the grounds and airspace of the White House in Washington DC are uncommon, but they do happen. On February 17, 1974, one occurrence ended on the White House lawn after a lengthy pursuit, not on the ground but in the air.

The chain of events that eventually ended at the White House started when US Army Private Robert K. Preston, who was training as a helicopter mechanic at Fort Meade in Maryland, was returning to the base after leave when he decided to stop at Tipton Army Airfield just south of Fort Meade.

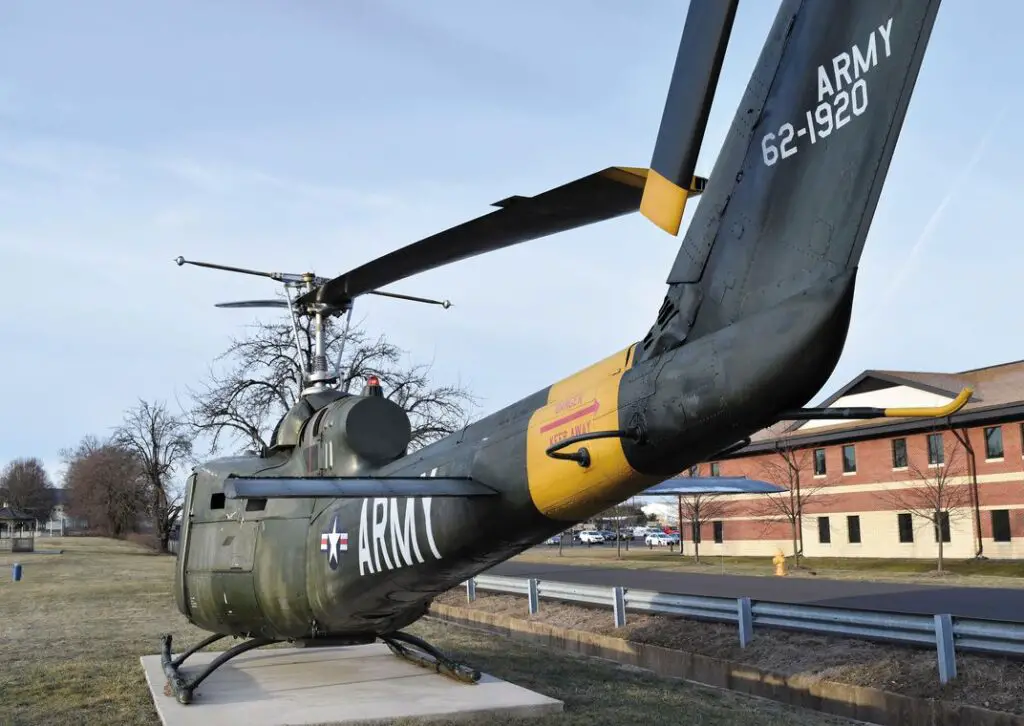

Thirty Bell UH-1B Iroquois “Huey” helicopters sat at the field, unguarded and fully fueled. Preston parked his car just after midnight, got into one of the helicopters, did a preflight check, started it, and took off, creating a chain of events that would eventually end at the White House.

It wasn’t Preston’s first time in a helicopter, but he hadn’t much experience. He had enlisted in the Army in 1972 and joined a four-year program that offered two years of helicopter training, and in return, he would have to enlist for two more years. Preston trained at a flight school in Fort Wolters, Texas, but didn’t finish after not passing the instrument phase of training. He was 20 years old with a private pilot’s license for single-engine fixed-wing aircraft and 157 hours of aviation experience but no rotary-wing certification.

Preston thought he had been unfairly washed out because the Army had too many qualified pilots since withdrawing from the Vietnam War. He was still on the hook for four years of service in the Army and was transferred to Fort Meade to train as a helicopter mechanic.

Before getting in the “Huey,” Preston had been at a dance hall and restaurant, feeling downtrodden due to a failed relationship and an uncertain future in the military. On how he was feeling at that time, he stated, “I wanted to get up and fly and get behind the controls,” and, “It would make me feel better because I love flying.”

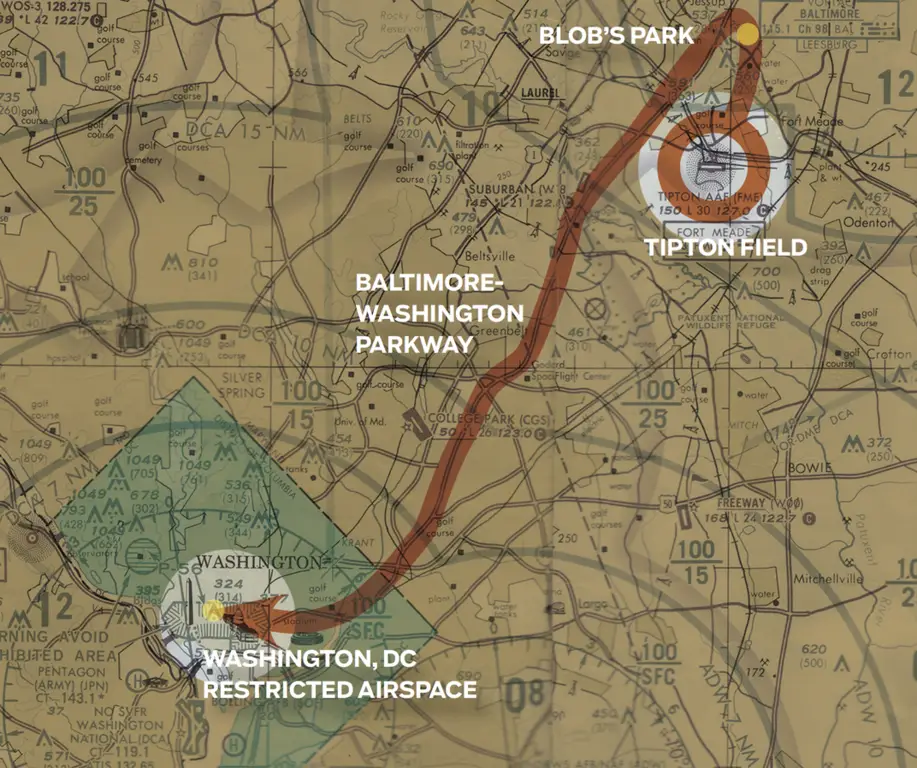

Preston took off from Tipton Field without the lights on and made no radio calls. A controller in the tower noticed the helicopter take-off and found no authorized flight plans filed. The controller then called the Maryland State Police.

Preston flew north and buzzed the restaurant where he had been earlier that night. He next touched down in a field in a nearby town, where his hat was later found, and then flew south toward Washington DC and the lights of the Washington Monument. After spending five minutes around the Washington Monument, even hovering just above the ground, Preston flew toward the Capitol and then to the White House. But this wasn’t when he landed there.

The Secret Service at the White House had been informed that a military helicopter had been stolen, but when Preston hovered over the South Lawn, they had no clear orders how to handle the aircraft. Shooting it down was part of Secret Service policy, but it was unclear if they should in this situation based on what might happen to people on the ground, and they were unable to reach their superiors for clarification.

Preston stayed there about ten minutes, and when nothing happened, he flew off. The Secret Service watch commander on duty decided that if the helicopter returned, they would open fire.

A controller at National Airport saw the helicopter on his radar near the White House and contacted the Washington Metropolitan Police Department, which dispatched a Bell 47G helicopter, but it wasn’t fast enough to keep up with the Huey as Preston flew it back into Maryland. From there, controllers at Baltimore-Washington International Airport had the Huey on their radar. They contacted the Maryland State Police, who dispatched two Bell 206 JetRangers to go after the stolen helicopter.

Preston led the Maryland State Police in an aerial pursuit as well as a ground pursuit. After flying over the Baltimore-Washington International Airport, Preston decided to give himself up, but he knew going back to Fort Meade would result in a court-martial and time in the stockade. So instead of that course, he came to the decision to give himself up to the President of the United States, Richard Nixon.

Preston continued to somehow evade the two skilled pilots of the Maryland State Police by flying erratically at different speeds and altitudes. He circled the Washington Monument one more time before heading back to the White House a second time. Preston just missed the steel fence surrounding the White House and began to put the Huey on the ground about 120 yards from the entrance.

The Secret Service did just what they had decided earlier if the helicopter were to return and opened fire on the Huey, striking it multiple times before it had touched the ground. Preston managed to land the helicopter even after being shot in the foot. One of the JetRangers from the Maryland State Police landed between the Huey and the White House.

Even after being struck by five rounds out of over 300 fired by the Secret Service, Preston was able to get out of the Huey and ran toward the White House before being tackled by Secret Service agents. He was handcuffed and brought into the White House for questioning. Preston asked to speak to President Nixon but found out that Nixon and his family weren’t even there.

Preston was taken to Walter Reed Army Hospital and then to DC Superior Court before winding up back at Walter Reed in a psychiatric ward. Even though it had been riddled with bullet holes, the Huey was still flightworthy, and Army pilots were able to fly it back to Tipton Field the next morning, and it was put in a hangar as evidence.

Preston was charged with unlawful entry on the White House grounds, a misdemeanor that carried a possible $100 fine and a six-month jail sentence. But his lawyers negotiated a plea deal, where the charges would be dropped in exchange for Preston to surrender to the military for court-martial.

At his court-martial, Preston was charged with the attempted murder of the President and the helicopter crews of the Maryland State Police. He also had several other charges tacked on as well. However, it was found during his trial that Preston had no intention of harming President Nixon. He contended that his only reason for stealing the helicopter was because he felt his enlistment, and being dropped from the helicopter training program, was unfair.

Preston pleaded guilty to wrongful appropriation and breach of peace and was sentenced to one year in prison and a $2,400 fine. The duration of his court-martial was taken as time served, and he would have to serve another six months, but Preston ended up serving two months at Fort Riley, Kansas, before being given a general discharge from the Army.

During a White House ceremony, Nixon congratulated the Secret Service watch commander on duty that night for giving the order to shoot down the helicopter, as well as the crew of the Maryland State Police helicopter that landed between Preston and the White House. He awarded them with pairs of presidential cufflinks.

Preston moved to Washington state after his release from prison. In 1982, he got married and raised two stepdaughters. He led a quiet life and died in 2009 due to cancer.

The Huey that Preston piloted was eventually returned to service after being repaired and transferred to the Pennsylvania Army National Guard to be used as a ground maintenance trainer. It was dubbed the “White House Special.” It is now on static display at Joint Base Willow Grove in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, though no placards state its incredible history.

Sources: New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, SOFREP