We’ve all experienced those chills that literally make our hair stand up. It could be from a beautiful piece of music, we could be scared, or we could just be cold. Of course, we call them “goosebumps,” the tiny bumps that appear on our skin when these things happen. But what is their purpose, and why do they show up?

As the name implies, goosebumps resemble the skin of a goose (or turkey or chicken, for that matter) after the feathers have been plucked out. You’ll see tiny bumps where the feathers once stood. What occurs on our skin looks similar, but it must be triggered by something to happen in humans.

There are three main causes for goosebumps: extreme temperature change, elicitation of some type of strong emotion, or the ingestion of some form of medication or ingredient that causes the reaction.

Goosebumps occur as an automatic response called the pilomotor reflex. This is an action of the sympathetic nervous system, the same one that gives us our “fight-or-flight” response.

Let’s go ahead and take a couple of examples of this response. Let’s say you get out of the pool on a hot summer day, and there’s a brisk cool breeze blowing. As the wind blows across the water left on your body, the temperature decreases rapidly through evaporation, making you suddenly feel cold.

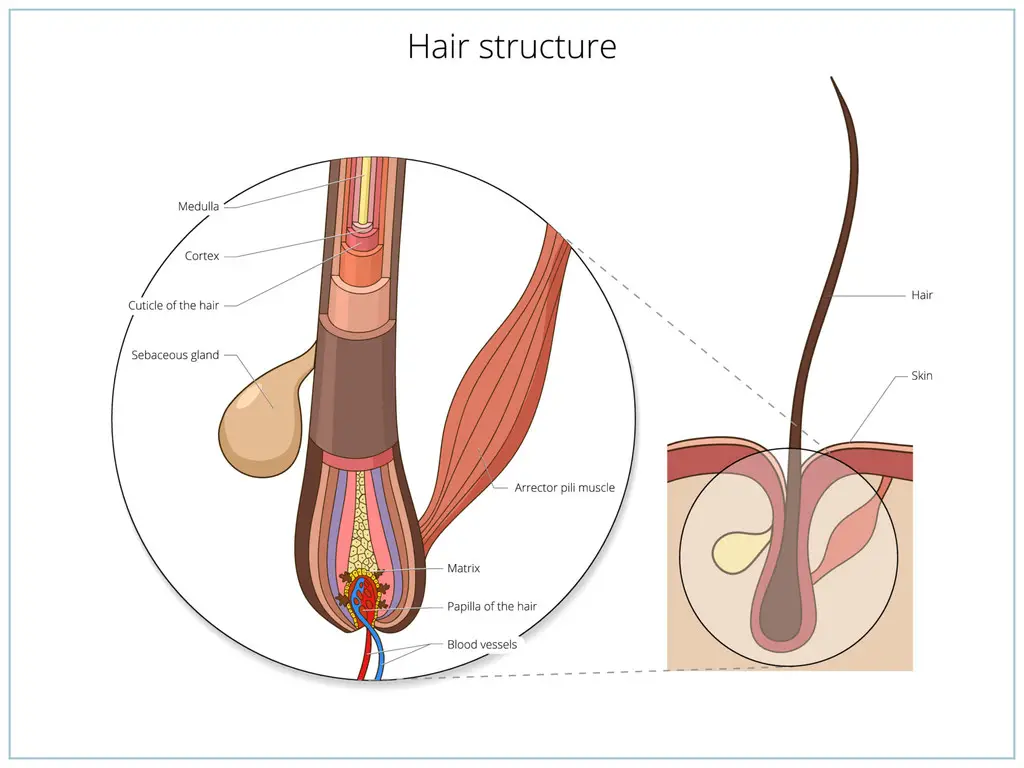

Your body’s response to this change is automatic. The hair on your arms and legs begins to stand up as the tiny arrector pili muscles that are attached to each hair follicle contract and cause the hair to straighten. This creates a depression on the skin around the hair follicle due to the contraction of the muscle, and the strand appears raised above the skin. But does this serve any purpose for our survival?

Not really, but it does for our fellow mammals. The goosebumps that occur from temperature changes are thought to be a product of evolution. When their hair stands up, it provides an additional area of air that acts as more insulation to the cold and can hold in heat better than if the hair was against the body. This process has become useless to us since we no longer have a thick layer of hair, but for other mammals, it’s still an important adaptation.

Another example can be taken when we’re afraid of something, such as the feeling someone is behind us in the dark. That’s always a good one. This fear response is similar to how an animal would be threatened. Again, during this situation, the sympathetic nervous system triggers a fight-or-flight response, and the arrector pili muscles once again contract, shooting those strands of hair straight out from the body.

You’ve probably seen this reaction in animals when they feel threatened. A cat’s hair will stand on end when it’s provoked or scared, for example. The reason is that this allows the animal to appear larger than what it is in the hopes of warding off danger. Many times the animal will change the position of its body or bare its teeth to get the strongest effect.

Our response may be different. We might not appear larger, but we might feel a surge of epinephrine (adrenaline) when it happens. The sympathetic nervous system has been triggered, telling us that something doesn’t feel right.

But goosebumps can also be elicited with feelings of euphoria or something that triggers a strong emotional connection, such as music, love, or a memory. The process of getting goosebumps in these situations seems to be caused by the action of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that controls the reward pleasure pathway of the brain. A study in the journal Nature Neuroscience found that dopamine was released in specific areas of the brain during musical pieces that elicited the “chills.”

Our bodies seem to be telling us something when we get goosebumps, and one last example where we need to listen to our goosebumps occurs with heat exhaustion. Goosebumps are a significant symptom during heat exhaustion when the body is overheating. It is also a precursor to the much more dangerous syndrome of heatstroke. This is one time when you need to listen to what your goosebumps are saying.

Sources: Scientific American, Livescience, Cleveland Clinic, NME, The Guardian, Nature Neuroscience